Stopping The Growth of The More Than 800 Homeless in Tallahassee

A New Era Dawns in the Quest to End Homelessness in Tallahassee

Tonia Miller felt her world was falling apart. An accomplished, college-educated business professional with two kids, the 43-year-old Navy veteran couldn’t believe what was happening. For the second time in her life, she was about to become homeless.

The first time, she was living in Jacksonville and managing a Blue Cross Blue Shield call center. It was 2009, and the nation was in the throes of the worst recession since the Great Depression. Like many other people across the country, she found herself laid off from work. To get by, Miller cashed in her pension and thought she could get along on that until things changed. She also thought that with her credentials and 25 years of experience, she would be a “hot commodity” and not have any trouble finding work.

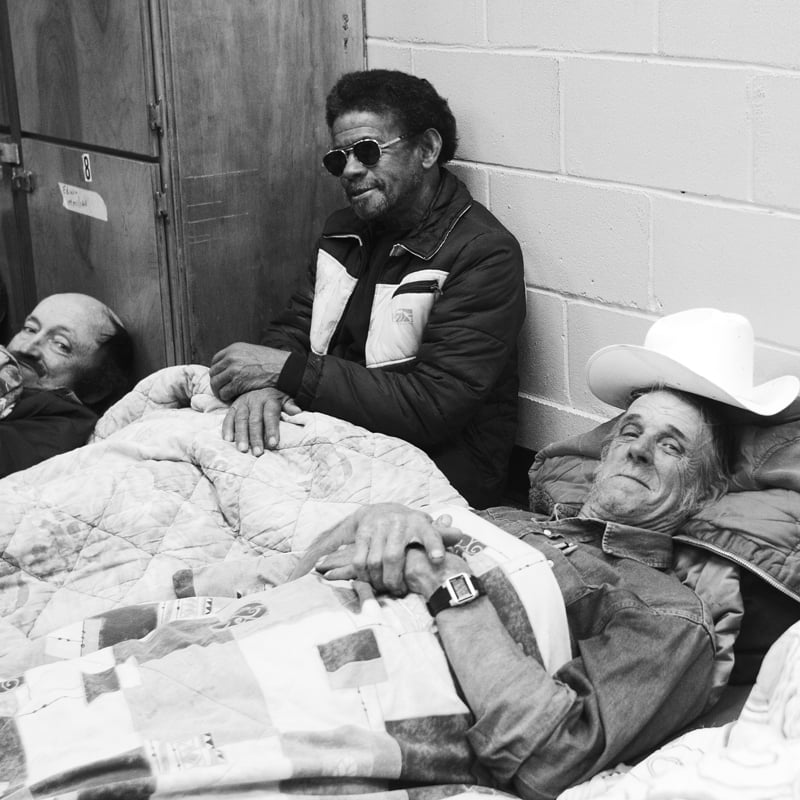

Mark Wallheiser/TallahasseeStock.com

Two men sleep under the Apalachee Parkway bridge in the shadow of the Capitol in December 1986, the year several homeless men died because of freezing cold weather in Tallahassee. |

It didn’t work out that way.

“When I was ready to return to work, work wasn’t there,” she said.

Sadly, Miller and her two teenage sons lost their home and spent the next four months in hotels, or staying with friends and relatives. They eventually moved back to Tallahassee, where she was born and where her mom still lived. Fortunately, Miller found work and happily set about settling in to a new life.

That lasted about a year. Then bad luck struck again when she got caught up in a company-wide series of layoffs.

She received unemployment, but in time it was exhausted. Then her kids turned 18 and she stopped receiving child support.

“I literally was without an income at all. I was at my wit’s end,” she said.

With the rent due and unable to pay it, Miller started looking for help. She turned to the 2-1-1 Big Bend referral service, which helps people in her situation connect with the resources that best fit their needs. But another quandary presented itself.

“They have this list of agencies that help people who meet a particular set of criteria, and none of them applied (to me),” she said. “The longer I spoke to them, the more hopeless I felt. Like, ‘Oh my God, now what?’”

Then the 2-1-1 adviser asked her one last question. Was she ever in the military? Well, yes, she was. And that’s how she was directed to the Big Bend Homeless Coalition, which connected her with a program that helps homeless veterans.

“It literally was like a lifeline of hope,” she said. “Here we were facing homelessness again. But part of Big Bend’s efforts is to prevent you from becoming homeless if you have a place already, and they work to try and help you keep that. And so they were a bridge for several months while I diligently sought work, and I became re-employed.”

The Face of Homelessness

Miller and her family were pulled back from the edge in the nick of time, but many people still need help.

In any given day in Tallahassee and Leon County, you’ll find some 800 homeless people. You see them on the streets, waiting for a bunk at The Shelter, or in remote camps out in the wilds of the surrounding area. Some are ill, both physically and mentally. Some are old and at the end of their rope. Some are down on their luck; they’ve lost jobs, been kicked out of their apartments or homes, or are fleeing a violent spouse. Some are kids that, while not “homeless,” are shuffled around from one family unit to another and live in a constant state of insecurity. Some don’t want help or don’t realize that help is available. But Tonia Miller’s case proves it can happen to anyone, anywhere, at any time. She said people who aren’t in that situation tend to make assumptions or draw the wrong conclusions about homeless people.

— Veteran Tonia Miller

“I think they assume that they are people who don’t work hard or there’s something wrong with them, or they may be looked upon like, ‘How do you allow yourself to be in this situation?’” she said. “But when you consider me, with a college education, I have almost 25 years of call center operations and management, and here I am, the new face of homelessness. You could be a professional person. You never know.”

Susan Pourciau, executive director of the Big Bend Homeless Coalition, knows that there’s no such thing as your typical homeless person, nor is there a one-size-fits-all solution to the problem.

For starters, 20 percent to 25 percent of the homeless population is what’s called “chronically homeless.” Those are people who have been homeless for a long time and likely have both mental health and substance abuse issues.

“For those people, the research and the experience is clear that the best way to help them get out of homelessness is to provide an apartment for them and help them in paying their rent,” Pourciau said. “To be able to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and get a good-paying job and live happily ever after — that’s not going to happen for that group. So we just need to be realistic. We don’t want people living on the streets or in our woods, which is where a lot of people live. But they do want to move into apartments if they get a little bit of help. And we have programs in our community that do that, and they are just wildly successful.”

Other homeless people might be survivors of domestic violence, and if they are leaving their home because they’re trying to get to a safe space they still qualify as homeless. That’s because they don’t have a place to stay.

“The people who are in the most unsafe situations go to Refuge House, which is our domestic violence shelter, but a lot of people come in to just the regular programs. Mostly women and children, and a lot of single women as well,” Pourciau said. “Those people need temporary housing and assistance getting out on their own. Many of them can work and the kids are in school. They just need help getting safe.”

Scott Holstein

Many nights, The Shelter was filled beyond capacity with people seeking a place to sleep. This photo is from 2007.

Another category of homelessness are the youth who have either been kicked out of their house or have run away, or even kids aging out of foster care, which is a pretty small number in our community, Pourciau said.

“We have one agency in town that is the primary provider for those young people, and that’s Capital City Youth Services. They have both emergency shelter and transitional housing, and they go out and find kids in the woods and on the streets as well,” she said. “Usually for youth who can’t be reunited with their families (there’s) transitional housing, (and) long-term housing programs that can help them learn life skills. And then they’re able to finish their education and get jobs, and they’ll be fine.”

Yet another category consist of families with children who are homeless because of job loss, a family breakup such as divorce, or an extreme health condition and no insurance. In short, the trouble that these people have gone through has stressed their financial stability and caused them to lose their apartments or their utilities. Pourciau guesses that 50 percent of the people who are homeless in our community fall under this category.

“For those folks, the best way to help them is to help them get a job if possible and provide rent deposits, utility deposits, and kind of help them with rent for a couple of months, and then they’re on their own. That model is called rapid re-housing,” she said.

Homeless veterans are another category.

“There’s lots of resources available right now, mainly through the federal government, to help veterans, so our community is doing a really good job of addressing veterans’ needs,” Pourciau said. “We’ve housed probably 300 veterans in the last year. Maybe 400.”

More can be done, but it all comes back to having the money to do it with.

“I know it’s a cliché, but it really is about the funding,” she said. “We have people who want to do the work, we know who the people are that need the help, and we know what programs work for different types of people. But without the money, we can’t put all that stuff together. Which is the frustrating part to those of us who work in that area. It’s like we know what to do … but can’t do it enough. We need something that can be scaled up to the level of homelessness that we have.”

All these various programs are funded by three main sources. There are private/community donations, the United Way and the Community Human Services Partnership, or CHSP. The CHSP consists of the city of Tallahassee, Leon County and the United Way of the Big Bend. They pool their money and give it out in grants to nonprofit organizations, Pourciau said.

“So it’s a combination of private and public money. Some organizations exist exclusively on private donations, others are primarily grant-funded, and there are lots in between,” she said.

The recession was another factor in the increase in homelessness, but it took time for those numbers to show up on paper because people held on as long as they could before the bottom dropped out under them.

“But it’s gotten better,” Pourciau said. “For instance, with our Hope Community residents, they’re able to find jobs much more quickly now than they were a couple of years ago. “We know from experience that people are having an easier time finding jobs, although they still don’t pay well.”

Story continues on page 2…

Seeking Shelter

When Tallahasseeans think about homelessness, the first thing that pops into their head is The Tallahassee Leon Shelter, which was founded more than 25 years ago in response to an emergency situation.

In the winter of 1986, several homeless men froze to death on the streets of Tallahassee. First Presbyterian Church was perhaps the first to take organized action and opened a makeshift cold-night shelter in the church basement. A few dozen men were given shelter and a fighting chance to survive.

At the time, no one truly recognized what had just happened. But this Christian offering of goodwill forever changed how the community dealt with the homeless.

A year later, according to The Shelter’s website, the actions of First Presbyterian spurred the creation of a makeshift facility called the Cold Nights Shelter. The original model for what would become The Shelter was hastily planned to help homeless people find temporary refuge during extreme weather, but it was soon apparent a larger need had to be addressed. The shelter’s services were expanded to year-round to give those stuck on the streets a place to go at night.

— Rick Kearney, founder of Mainline Information Systems and The Attitude Foundation

Two years later, The Shelter opened its doors and became a certified agency of the United Way of the Big Bend. And the number of people seeking shelter began to escalate.

“When I first started working here, every now and then we would check in over 200 people,” said Jacob Reiter, executive director of The Shelter. “But now that’s the norm.”

In 2013, The Shelter provided 80,435 lodging nights and currently averages between 220 and 240 clients each night. During the coldest nights of the year, a special men-only Cold Night Shelter is opened at a local church that can handle 50 to 60 homeless men.

For more than a quarter century, The Shelter did what it could to help the homeless, but it was always a struggle, and its existence was never without controversy. Then, in February 2013, it was rocked by scandal that really put it under the microscope.

When Renee Miller, owner of City Walk Urban Mission (a separate organization), started to hear complaints from her clients about The Shelter, she was tempted to dismiss them — at first.

“When you are in a bad situation, you just tend to exaggerate things,” she said. “I tend to exaggerate things when I am in a bad situation, so I just took it with a grain of salt and considered the source.”

City Walk is a Christian mission effort to transform former inmates into productive citizens through housing, clothing, mentoring, counseling, job placement and family structure. Concerned for the people she was trying to help, she took on a daring task: going undercover as a homeless person to see for herself what, if anything, was going on.

She didn’t know what she was going to find. Turns out, she got more than she bargained for when a Shelter employee “propositioned” her.

|

Homeless in Leon County 805 — the number of homeless people in our community on any given day. 62% have a disabling condition (including physical, medical, mental health, substance abuse, HIV/AIDS and development disabilities). 188 are sleeping outside. 44% have been homeless for a year or more. 34% have been homeless four or more times in the past three years. 17% are military veterans. 25% were found “medical vulnerable” and at risk of dying. 71% have no medical insurance. 25% have higher education. Source: Big Bend Homeless Coalition |

“I didn’t really think I was going to go and uncover a bunch of dirt or anything. I really thought I would find maybe some things that could be better, but I never thought in a million years that I would experience what I experienced in my three hours there,” she said.

Miller’s experience prompted a police investigation, but ultimately the allegations were ruled “unfounded.” However, that conclusion didn’t stop the United Way and The Shelter’s board of directors from being alarmed by certain parts of a police report, which indicated a pattern of inappropriate contact and treatment of some clients by the staff.

In the wake of the police investigation, longtime Shelter founder and director Mel Eby (who had just been named the Tallahassee Democrat’s Man of the Year) retired and was replaced by Reiter, who had worked in the Tallahassee homeless service community since 2007. Two other employees were fired and four women were hired to work in “overnight, evening and daytime operation positions.”

Meanwhile, both The Shelter board and the United Way realized an independent study was needed to take a closer look at the operations and make recommendations for improving service. A group of analysts from the University of Central Florida’s Institute for Social and Behavioral Science were called in, conducted interviews, and released a report in April 2013.

The team of analysts came up with 12 recommendations. They called for The Shelter’s board of directors to increase its membership and improve accountability and transparency. Another recommendation called for The Shelter to change its “shelter-only model” into a “first step” program that would stop enabling homelessness and start getting people back on the road to self-sufficiency.

Their biggest suggestion called for city and county officials, along with the United Way of the Big Bend, The Shelter board and other interested parties, to join forces and build a homeless shelter in a new location. The new shelter would provide a safer and more secure environment for workers and homeless individuals alike.

That effort is currently under way. Groundbreaking for the new shelter took place in February 2014. It’s located on West Pensacola Street between Goodwill and the Big Bend Homeless Coalition. The new facility is called the Comprehensive Emergency Services Center (CESC), and it’s expected to be completed this March.

Photo courtesy Clemons, Rutherford and Associates Inc.

When complete, the Comprehensive Emergency Services Center will have the capacity to provide food and shelter for nearly 400 men and women.

The CESC will not provide housing for families. Instead, it will focus on single men and women. Hope Community, a division of the Big Bend Homeless Coalition, will take over all of the family housing. Hope Community is phasing out its men’s facility and converting its dorm into family-friendly living spaces.

During the groundbreaking ceremony for the CESC, Deborah Holt, chairwoman of the board of the Tallahassee Leon Shelter, described the need for not only a safe shelter but a place for counseling and referrals as well.

“We humans need to rest to recharge our batteries. We need to be safe while we rest, and we need to perceive that we are safe, believe that we are safe, so that we can face the challenges of the next day,” Holt said. “A principal goal for this new facility is to provide that safety for those who rest or work here. Folks without a place to stay can come here and get their second wind. They can get medical attention, education, counseling, referrals to more services, plus a bed to rest in and three good meals, all under one roof.”

Rick Kearney, founder of Mainline Information Systems (a Tallahassee-based consulting firm focused on IBM products) and The Attitude Foundation, donated more than $3 million for construction, although the final price tag is estimated to be in the $5 million to $6 million range.

“I was always one of these people that was like, ‘Come on, let’s do something, let’s go out and do this,’” he said.

Scott Holstein

A $3 million donation from businessman Rick Kearney to fund a new shelter kickstarted a new era of cooperation between local groups providing services to the homeless.

Behind Kearney’s effort is the creation of a model for homeless care that other regions can follow.

“One of our precepts for everything we do is; ‘Is this something Panama City can do, that Lake City can do, that Tampa can do?’” he said. “Anybody can do it if they just muster the existing resources and put them together in new ways, in a better way than what they are doing.”

Taking Action

This can-do spirit is the driving force behind Kearney’s — and many others’ — big plans. In his case, he saw a problem and decided to try to fix it. He did not see a lack of resources as the main problem.

“There are enough resources already in society, if you just organize them correctly to do things like this. But up until now it’s not been organized,” Kearney said.

This spirit of optimism has characterized not only the CESC but the entire community’s effort to help end homelessness.

“I think the main change that has already started happening is that all programs should be geared toward ending homelessness, not managing it,” said Pourciau, the Big Bend Homeless Coalition director. “So it is a difference in philosophy that dictates different programs.”

That’s exactly what is happening. The new shelter program has reinvigorated a community effort to end homelessness. Program directors are putting their heads together, revamping each organization and focusing on a permanent solution.

Tallahassee City Commissioner and Big Bend Continuum Care Board member Gil Ziffer became interested in working on the homelessness issue after his wife, Gail Stansberry-Ziffer, suffered an unexpected fall, resulting in a shattered femur and a broken hip.

While recuperating at Tallahassee Memorial Hospital, Stansberry-Ziffer shared therapy sessions with a homeless Vietnam veteran who had been hit by a car. She soon discovered that he had been living at The Shelter for 18 years.

“In the process of being his neighbor for two weeks, we got to know him … and we have, since that time, done everything we can to try to help him,” Gil Ziffer said.

For Ziffer, this experience was the spark that lit the fuse. In 2013, when it was obvious there had to be a change, all the pieces began to fall into place. Ziffer, Kearney, Florida State University Associate Professor of Social Work Tomi Gomory, Renaissance Community Center Director Chuck White and a number of other community leaders sat down at a Tallahassee Community Redevelopment Agency meeting with open minds and a desire for change.

“There was something different this time,” Ziffer said. “Because of Renee Miller and because The Shelter had some fire marshal issues, we could only allow it to continue in its current condition for a certain amount of time.”

Ziffer said all sides were able to sit down, lower barriers and make something happen. Stakeholders met and developed a plan for moving The Shelter. The Tallahassee Community Redevelopment Agency decided to buy the old Shelter property while the city finalized the land purchase on Pensacola Street for the new shelter site. The CRA got involved because the city is interested in upgrading that area, but no formal plan has been adopted yet.

Even with all of these groundbreaking developments, one difficulty remained: Each homeless person has a different story and different needs. As a result, planning for those needs is tough. Gomory, a board member of The Shelter, referred to it as “decision making under uncertainty.” But Pourciau said that over the years, certain plans have proven to work, even though it is a multi-faceted problem.

“Everybody has their own story, so everybody is unique, but in terms of designing a system that will help people get out of homelessness, there are some general things that we know work,” she said.

A New Mission

This sense of collective urgency was a long time coming. Until now, no one organization had the ability to do every little thing effectively. They were also vying with each other for limited funds rather than working together. Gomory said city efforts to improve the coordination of services goes back to 2010. But Kearney’s generous donation was a game-changer.

“Since there was a private benefactor, the competition for money has all been taken out of the loop,” Gomory said.

“You will find wherever you go that when people break down their barriers and think, ‘OK, maybe I need to change,’ good things happen,” Ziffer said. “If people come into a meeting with a closed mind, then there’s no point.”

This new outlook has allowed The Shelter, the Big Bend Homeless Coalition, Capital City Youth Services and major universities to work together and create a solution for homelessness in Tallahassee rather than just managing it.

Matt Burke

A new Drop-In Center funded by CCYS provides a place for homeless youth to find services and a helping hand.

All of the organizations involved in this effort bring something new and unique to the table and make up for what others lack, Pourciau said. Before they were working together, the programs they had in place were not effective plans for getting people back into stable situations.

“If you manage homelessness, you will have a certain kind of program, but if you are working to get people out of homelessness, you will have a different kind of program,” she said. “I think that our agency and others are making that shift. Now, for instance, we have a lot more programs than we did five years ago that are geared toward keeping people in apartments rather than just making sure they have a shelter.”

This new collaboration has already drawn attention from outsiders.

“We have had visits from representatives from a number of communities throughout Florida, as well as other states, who want to see for themselves exactly how such a cooperative and coordinated service delivery system actually works,” said Renaissance Community Center director White. “These include Jacksonville, Orlando, Panama City and Miami. The National Coalition for the Homeless, located in Washington, has also had representatives visit Tallahassee to observe operations. I believe that the answer to reducing homelessness must include a cooperative, collective, collaborative and comprehensive approach to each individual experiencing homelessness.”

Tonia Miller, in particular, is relieved to be a former client of the Big Bend Homeless Coalition.

“I can’t say enough about what they do to change the direction and lives of families,” she said. “They literally came in and made a difference in our lives so that we didn’t have to go through something so horrific. Again.”

Mikaela McShane and Megan Williams contributed to this article.