Revealing George Floyd

Former Tallahassean wins coveted prize for portrait of a victim of police violence

In May 2020, the entire world got to know the name George Floyd, but it would be another two years before we would meet Perry.

The murder of Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin led to a new wave of civil rights activism. His death took on a life of its own, sparking international outrage, domestic debate, protests, legal reforms and difficult dinner table discussions. Amid a series of incidents of police violence against Black Americans and in the midst of fear and uncertainty fomented by a global pandemic, Floyd’s murder became a cultural tipping point.

Long before he arrived in Minneapolis, Floyd lived as a boy in Houston at a tired housing project and went by his middle name, Perry. As the world became aware of George, his family mourned the Perry known only to them.

“It became this public spectacle, and (Floyd’s) friends and family members had to grieve in public before they even knew what was happening,” said Toluse (Tolu) Olorunnipa, Washington Post White House bureau chief and co-author of His Name is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice.

“A movement was already underway, and they found themselves cast into the front lines,” Olorunnipa said. “We talked to them in the middle of that, and we also spoke to them in the quiet hours, weeks and months after. The cameras and protests had died down, and they were left to deal with their emotions.”

For Olorunnipa and co-author Robert Samuels, both of whom are Black, writing His Name is George Floyd served to answer two overlooked questions: Who was George Perry Floyd, and what was it like to live in his America?

The writers pored over historical documents and public records and conducted more than 400 interviews with family members, friends, police, political leaders and activists. The result of their work is a thorough, insightful, deeply human account of a loving, though flawed, man and a world often set against him.

The book earned its authors the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction. It was also a finalist in the biography category.

Olorunnipa grew up in Tallahassee as the son of Nigerian immigrants. His father was a scholarship student at the University of Illinois before joining the faculty at Florida A&M University.

While at Florida High, Olorunnipa played sports, participated in student government, wrote for the student newspaper and idolized Florida State football players.

“When I was about to leave high school, I was looking for any way to get money to try to pay for college,” Olorunnipa said. “My parents already had a couple of kids in college, and money was tight. It was pretty clear that I was going to need to shoulder some of the burden myself if I was going to go to college. Then I heard about a scholarship opportunity at the Tallahassee Democrat.”

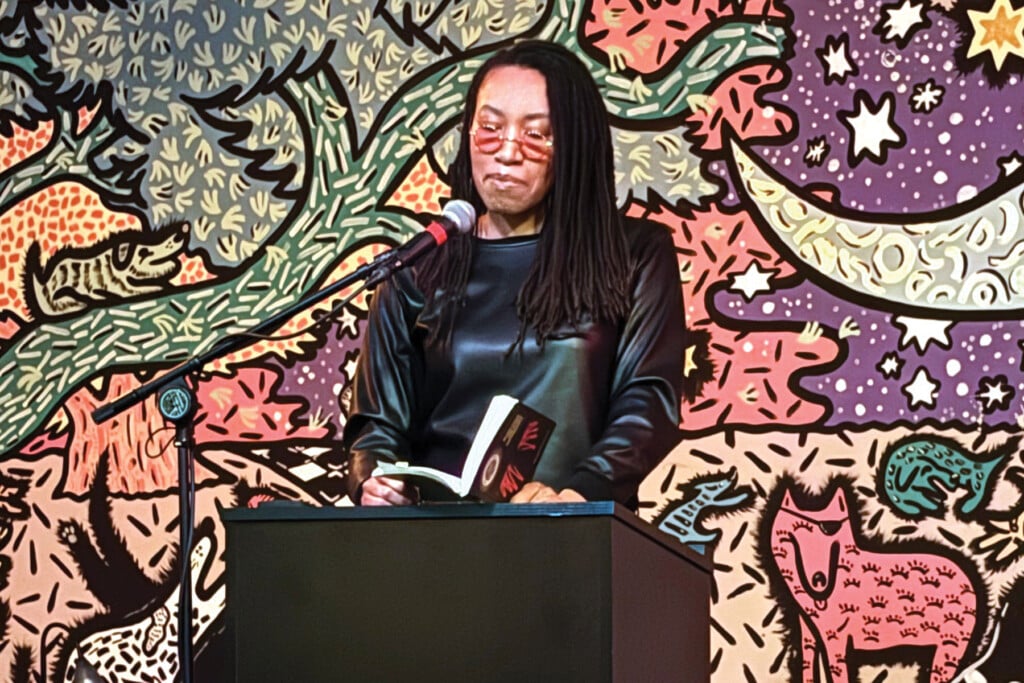

As the son of Nigerian immigrants, Toluse Olorunnipa had to find a way to help fund his college education. A scholarship from a newspaper group helped. Photo by Lori Hoffman / Bloomberg

Olorunnipa submitted his writing, met with the editor and was awarded a local scholarship by the Democrat, but his success did not stop there. He went on to win a national $40,000 scholarship from the paper’s then-parent company, an award that enabled him to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in sociology at Stanford University.

By the time Olorunnipa started his first job at the Miami Herald in 2009, the newspaper industry was struggling and newsrooms were shrinking. Olorunnipa felt fortunate to have a job.

“I loved what I was doing,” he said. “But as much as I was able to tell really impactful stories, as much as I was getting my feet wet learning to write stories that would make a difference in people’s lives, help people get information and hold powerful people to account, I was living in a termite-filled apartment that I could afford in a rough neighborhood.”

Olorunnipa found his journalistic niche by giving voice to the voiceless, including a Caribbean woman who called the newspaper frantic and afraid she would lose her home. Starting with that woman, Olorunnipa uncovered a massive foreclosure fraud scheme.

He returned to Tallahassee to cover state government for the Herald and later became the Bloomberg correspondent reporting on the Florida Legislature. He made waves with a series of articles about corruption and misuse of taxpayer dollars by Citizens Property Insurance Corp. These and other stories launched Olorunnipa’s national career. He traded Florida’s capital for the nation’s capital, accepting positions covering the White House for Bloomberg and later the Washington Post.

“I had huge imposter syndrome, but I tried to just put my head down and do the work,” Olorunnipa said. “I tried to make as few mistakes as possible while also drinking from a fire hose and trying to learn as much as possible.”

While Olorunnipa’s career has taken him all over the country and the world, he views his Tallahassee upbringing as foundational.

“I think growing up in Tallahassee helped me have that sense of right and wrong, that sense of grounding so that I would be able to address politics from a perspective of someone who came from somewhere where everyday people are trying to make ends meet and need a little help,” Olorunnipa said.

Dreams Derailed

As a young man, Perry, as family called him, had outsized aspirations — to become a Supreme Court justice, a pro athlete or a rap star. By the time his world came crashing down in the months before his death, he had been chasing more modest ambitions — a little stability, a job driving trucks, health insurance. Still, in his dying seconds, as he suffocated under a white police officer’s knee, Floyd managed to speak his love.

“Mama, I love you!” he screamed from the pavement, where his cries of “I can’t breathe” were met with an indifference as deadly as hate.

“Reese, I love you!” he yelled, a reference to his friend Maurice Hall.

“Tell my kids I love them!”

These words marked the end of a life in which Floyd repeatedly found his dreams diminished, deferred and derailed in no small part because of the color of his skin.

— From His Name is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Publisher Penguin Random House rates the Pulitzer Prize winning book by Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa “a landmark biography that reveals how systemic racism shaped George Floyd’s life and legacy — from his family’s roots in the tobacco fields of North Carolina, to ongoing inequality in housing, education, health care, criminal justice and policing — telling the story of how one man’s tragic experience brought about a global movement for change.”

Publisher Penguin Random House rates the Pulitzer Prize winning book by Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa “a landmark biography that reveals how systemic racism shaped George Floyd’s life and legacy — from his family’s roots in the tobacco fields of North Carolina, to ongoing inequality in housing, education, health care, criminal justice and policing — telling the story of how one man’s tragic experience brought about a global movement for change.”