A 19th-Century Story of Disloyalty, Gunplay, Lawsuits and a Mysterious Death

Scandal in Old Tallahassee

About this story

Charles Chaires, the son of Florida’s first millionaire, despite his vast inherited riches, proved unable to deter his wife Martha’s affections for his nephew, Ben. The illicit union produced a child and estrangement. It seems that things went awry as soon as Charles carried Martha away from the relative refinement of Duncanville, Georgia, to the isolation of Leon County.

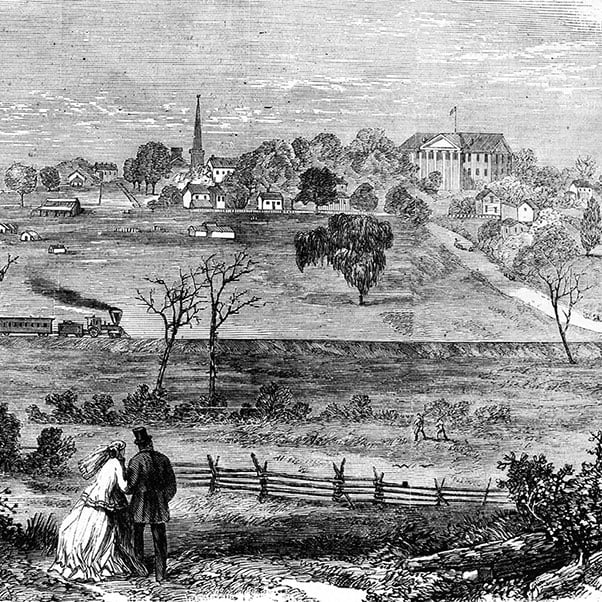

State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory

Under a blanket of pine needles, a solitary grave marker rests in a lonely corner of a small rural churchyard. It bears this simple inscription: Martha Chaires Thomas/Feb. 18, 1842–Nov. 2, 1911.

The sparseness of the words belies the complexities of a life marked by scandal and disgrace. This is Martha’s story, and it begins long before her birth with the prominent Florida dynasty she was to join and disturb.

The story of the Chaires family and its intrigue was lost to history until it was recently uncovered by research into official documents, old news clippings and other historical records. This complex tale of human frailty, greed and jealousy reveals that scandals surrounding power, prestige and family are not restricted to modern society.

Son of Florida’s First Millionaire

Martha’s future husband, Charles Powell Chaires, was born in 1830 in Leon County, the youngest son of Benjamin and Sarah Chaires’ 10 children. Benjamin Chaires was Florida’s first millionaire and an influential territorial pioneer. When Charles was 8 years old, his famous father died at Verdura, the family’s ancestral plantation in southeastern Leon County on land now owned by the St. Joe Company near the SouthWood development. Charles was to become Verdura’s owner, and the property was to remain in his estate until it was declared insolvent — a decline in which Martha played a role.

As Charles grew up on the family farm, his siblings left to establish plantations and families of their own, finally leaving him and a brother as the last family members residing in the grand mansion. The two lived at Verdura until about 1851, the year of Charles’ first marriage to Sarah Ann Raines. By 1861, Charles had established his second plantation, Ever May, also in Leon County, located east of the present-day Capital Circle, roughly between Old St. Augustine Road and U.S. Highway 27. He had also purchased property and had business interests about 100 miles to the southeast in Cedar Key on the island of Atsena Otie.

Though Sarah is buried in the family graveyard at Verdura, the year of her death is unknown. What is known is that on July 23, 1867, Charles married Martha Mash at the “palatial” home of her planter father, Maj. Jackson J. Mash, in Duncanville, Georgia (near the present community of Beachton). With her marriage to Charles, Martha was transplanted from her father’s socially elite circle to the rough seacoast town that was Cedar Key and to the lonely life of a rural plantation mistress in Leon County. In a later letter to Charles’ brother, her depression is clear: “I never … have felt so desperately unloved, unappreciated and neglected for so long a time.”

After nine years of marriage, in 1876, Martha’s dissatisfaction with her life took a drastic turn, one that became painfully public in 1880, when Charles petitioned the Leon County Court to dissolve his marriage to Martha Mash. The petition began with a startling charge: adultery. Charles asserted that in January 1878, he had returned to Ever May and discovered that his 35-year-old wife was pregnant. He knew immediately the baby was not his.

Martha refused to reveal the identity of the father, telling Charles only that “he knew.” Stunned, Charles said he thought Martha “too pure for anything of this kind” and evicted her from their home, forcing her to go to her parents’ residence in Thomas County. A month later, she was back, begging to come home and admitting that she had not told her parents the true reason for “visiting” them. Charles did.

When he took her back, he told her father he wanted to “do the honorable thing.” The plan was for Charles to take Martha with him on the first leg of an upcoming business trip. She would give birth in New Orleans, place the baby in an “asylum,” and then he would take Martha to Tennessee, where she would establish a school. Charles would then continue on his trip to Ohio.

The Secret Lover: Uncomfortably Close

While Martha was in Tennessee, Charles was suspicious that Ben visited her. Martha’s written defense shows gossip was flowing: “I can send you a certificate from this family (with whom she boarded) that he made me no visit while here. It was by a mere accident that I even heard that he was here. If I am not mistaken, he only remained one night. If he told Bro. Tom he wanted to see me before leaving Florida he certainly changed his mind.” Eventually, Charles discovered the affair had been going on since February 1876.By the time Charles arrived in Ohio in late May, he had learned the identity of his wife’s lover: his 31-year-old nephew, Benjamin Cadwallader Chaires, son of Charles’ older brother Benjamin Chaires Jr. Ben, the nephew, lived close by. His plantation, Fauntleroy, was adjacent to Ever May, where he often attended to Charles’ mules, a point made in court hearings on the dissolution of marriage.

While Martha was in Tennessee, Charles was suspicious that Ben visited her. Martha’s written defense shows gossip was flowing: “I can send you a certificate from this family (with whom she boarded) that he made me no visit while here. It was by a mere accident that I even heard that he was here. If I am not mistaken, he only remained one night. If he told Bro. Tom he wanted to see me before leaving Florida he certainly changed his mind.” Eventually, Charles discovered the affair had been going on since February 1876.By the time Charles arrived in Ohio in late May, he had learned the identity of his wife’s lover: his 31-year-old nephew, Benjamin Cadwallader Chaires, son of Charles’ older brother Benjamin Chaires Jr. Ben, the nephew, lived close by. His plantation, Fauntleroy, was adjacent to Ever May, where he often attended to Charles’ mules, a point made in court hearings on the dissolution of marriage.

A year after his return from Ohio in October 1879, Charles wrote his will. Then on Nov. 17 in downtown Tallahassee, he and his nephew engaged in what a local newspaper referred to as a “shooting affray”:

“Yesterday on Monroe Street, an encounter occurred between Ben C. Chaires and C.P. Chaires, in which several shots were exchanged, resulting in the wounding of the former in the left leg below the hip. The encounter was the result of a feud of long standing, growing out of domestic troubles. Mr. Chaires’ wound is not considered a dangerous one. Both parties were promptly arrested, which, perhaps, prevented more bloodshed.”

Both men were indicted for “carrying secret arms,” and Charles was indicted for “assault with intent to murder.” Charles was imprisoned in the Leon County Jail until Dec. 4, 1880, when three associates put up bond to free him until the scheduled March disposition of the case. At that time, the indictments for carrying secret arms were transferred to the Leon County Justice of the Peace, and Charles’ indictment for murderous assault was dismissed.

On the same day that assault charges were dropped, Martha responded in the judge’s chambers to Charles’ charges of adultery. She stated that she had told him she was pregnant in September 1877, that she had lived with him executing her wifely duties until after the birth of the child, and that on his return from Ohio he had “kept himself aloof from her.” She had nothing to say, though, about what happened to the baby or why, if it had been Charles’ child, she left it in New Orleans.

Charles’ testimony later that year defied Martha’s version — and pulled no punches. He said they had lived apart since January 1878, and the cause was “her adultery with Ben C. Chaires at my residence on the Ever May Plantation in this county.” He also claimed that she had confessed everything.

A Mysterious Death, a Lingering Lawsuit

Charles died — mysteriously — at the St. Marks Lighthouse on Aug. 17, 1881, before the judge decided the case. His newspaper obituary — which did not appear until October — cites an incorrect date of death and offers no cause. According to a family story, Charles died of yellow fever, but this story’s many inaccuracies make the cause of death uncertain. Other facts are intriguing but not helpful: The executors of his estate paid the lighthouse keepers on Aug. 21 for “attention to Mr. Chaires,” and they paid individuals for hunting down and caring for his horse.

Charles is said to be buried in the graveyard at Verdura, but his grave marker is not visible today. He had purchased a plot in the cemetery at Atsena Otie Key, but it is doubtful his body would have been transported such a long distance in the summer heat.

It is not surprising that Charles did not include his estranged wife in his will, nor perhaps that Martha petitioned the court for dower from Charles’ estate. The executors made every attempt to keep her from benefiting. Litigation dragged on for 15 years before she was finally awarded acreage from the Ever May and Verdura plantations and income from both properties.

For once, hearsay worked in her favor. No one except Martha and Ben (who refused to testify) had firsthand knowledge of their affair — all other testimony the court considered hearsay, insufficient to refuse Martha her widow’s due.

Epilogue

Verdura Court costs associated with Martha’s dower petitions, the decline in cotton production and heavy mortgage debt resulted in the insolvency of Charles’ estate in 1896. The only solution was to give Verdura over to creditors, and the plantation passed from the Chaires family. The ruins of the once-grand home are still visible but not accessible to the public.

Ben Benjamin Cadwallader Chaires continued to live and farm at Fauntleroy. He was a member of the 1897 Florida Legislature and became a well-respected resident of Leon County and the father of four daughters and one son. He died May 2, 1902, from “acute indigestion” (possibly appendicitis) and is buried in St. John’s Episcopal Cemetery in Tallahassee.

Martha In 1906, Martha married her sister’s widower, William Frank Thomas, in Thomasville. Although both daughter and widow of wealthy plantation owners, she was nevertheless working before the marriage as a “matron of sanitation.” She was a landlady when she died from a respiratory illness on Nov. 2, 1911. Martha’s grave is in the New Ochlocknee Baptist Church cemetery in Beachton — alone with neither of her husbands nor with family. Her parents, second husband (interred next to his first wife), and other family members are buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Thomasville.

Editor’s Note: This story was researched and written by Sharyn Heiland as part of her work on her master’s thesis in historic archaeology at Florida State University.