A Woman of Many Cultures

Author Faith Eidse finds great value in listening

Rather out of nowhere, a mention of the Emerald Coast Zoo in Crestview occurs in Faith Eidse’s stirring, coming-of-age memoir about her childhood spent in Canada and the African nation formerly known as Congo.

Eidse was 8 years old when young militants called Jeunesse began terrorizing the countryside in Congo. They were not satisfied that promises made when their homeland gained independence from Belgium in 1960 had been fulfilled, finding instead that the country was still effectively ruled by colonialists.

As white people, Eidse, her three sisters and her Mennonite missionary parents were vulnerable to attack and made preparations to flee their home in Kamayala.

Before they departed, Eidse “heard a familiar trumpeting from the savanna” and wondered, “Were those elephants guarding us?”

Decades later, Eidse, a Tallahassee resident since 1992, heard the same trumpeting again, this time at a wedding that took place at the zoo in Crestview.

“It rose, a deep whoo-ooo from the lion’s cage just as the groom spoke his vows,” Eidse writes in Deeper than African Soil (Masthof Press, 2023). “Those had never been elephants encircling us, but lions all along.”

The passage points to two realities about Eidse’s childhood. She grew up unaware of some of the dangers in her midst. And, the greatest threats to her safety and existence were posed not by the natural world, but by humans.

The Eidse family would escape harm by the Jeunesse, whose rebellion was defeated. But Eidse would sustain physical, emotional and psychological abuse at the Mennonite hostelry/school in Leopoldville that she attended as a child and teen. There, a school parent, “Uncle Hector,” attempted to thwart every natural inclination of students to achieve an identity and express themselves.

Deeper than African Soil is a book about suppression, subjugation, submission and people whom Eidse refers to as “healers of the soul.”

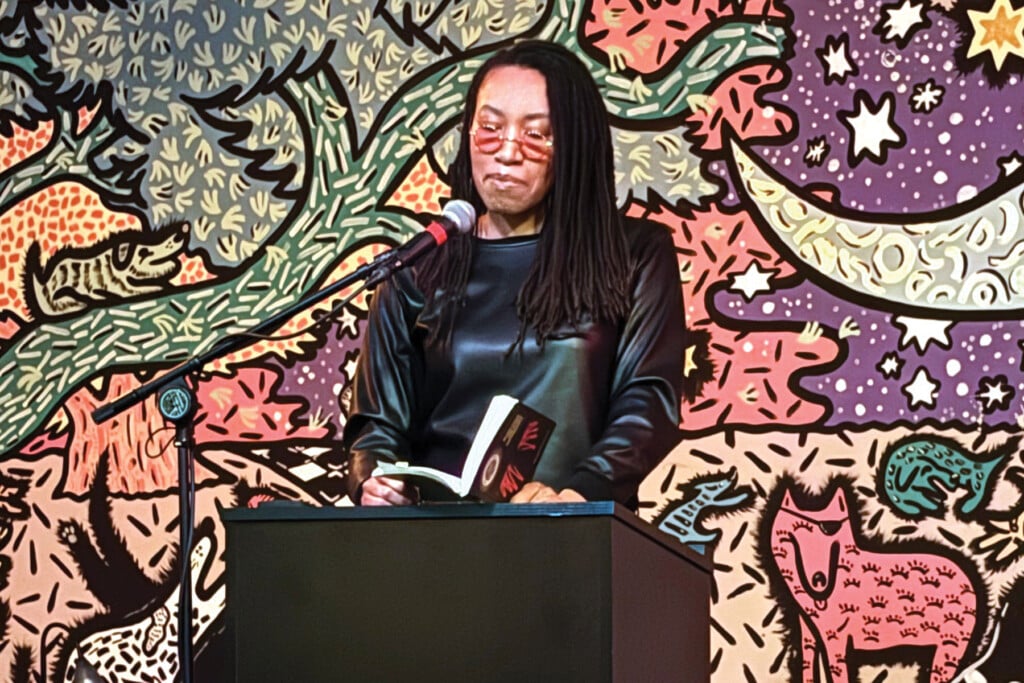

Eidse has written a memoir, Deeper than African Soil, and edited a collection of memories and anecdotes titled Voices of the Apalachicola. Photo by The Workmans

Her parents enforced strict rules regarding skirt lengths, books, music and boys in raising Eidse and her three sisters, Hope, Charity and Grace. Eidse was more inclined to challenge them than her siblings but found at school an environment that was even less relaxed.

Informed by Uncle Hector that he wanted to see her, Eidse racked her brain, trying to figure out the offense she may have committed.

“Let’s start with the way you dress,” Hector said as the meeting began. “You wear those jeans so tight, you turn men on when you walk. You do it on purpose. You’re a whore, a slut, a prick tease.”

When Eidse missed supper at her dorm for having (platonically) visited a boy at a nearby school, Uncle Hector notified her parents. Her father arrived and whipped her with his belt, at least in part, one suspects, to impress the school parent.

Chief among Eidse’s soul healers was a woman who was hired to relieve Uncle Hector of any responsibility for supervising girls. Eidse describes Shirl as a “chestnut-haired social worker with Liza Minelli eyes who lived with us and joined us during fetid afternoon gab sessions when it was too hot to move or study. She propped her feet on the walls and never enforced rules against doing so.”

In addition to being relatively cool, she served as a buffer between Uncle Hector and girls he had abused.

Students at the hostelry passed around pirated copies of Les Girls and The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test and found ways to listen to Bob Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel, Carole King and Creedence Clearwater Revival.

Nature abhors a vacuum. Books and music abhor a barrier. Those barriers, once permeable, are sieves today.

For Eidse and her sisters, the outdoors was a source of joy and recreation. The girls knew the best swimming holes in the Kamalaya River, and Eidse recalls with fondness the time she, Hope and Charity, guided by a notorious female hunter, Mama Beya, intercepted a deer fleeing a grass fire and dispatched it with hand tools. Nor could she resist mentioning the 3-inch-long roach that dropped from a ceiling and landed in her mouth.

As a child of 12, Eidse toured Europe with her family en route from Africa to Canada. She visited the Hohenzollern Castle near Stuttgart, Germany, where her dad bought her a souvenir keychain that she has cherished ever since. Photo by The Workmans

Eidse earned a doctorate in creative writing from FSU in 1999. She moved to Tallahassee with her husband, Philip Kuhns, a physicist, when he landed a job at FSU’s MagLab.

She regards herself as a “third culture kid,” having lived in Canada, Africa and the United States.

“I believe that there are many faiths from which to draw wisdom,” Eidse said in an interview with Tallahassee Magazine. “For sure, I am not a fundamentalist. Having grown up among various cultures, one thing I always come back to is the value of being open to and learning from people from other walks of life.

“I’m an amalgamation. I’m not one thing from one place. But my African culture claims me, and that’s cool.”

Eidse may have come by her spirit of inclusivity from her parents, Helen and Ben Eidse, their narrowness in some areas notwithstanding.

“He learned a lot from other people; he wasn’t didactic,” she said about her father, who was a missionary, linguist, community organizer, handyman and mechanic. “He asked people around him to tell him about their experiences, their stories, their cultures, their parables. He believed in the power of stories as a conduit for truth.”

Helen was a healer.

“Africans said about her that she was the one who would sit with the sick and the outcasts, the leprosy patients when no one else would,” Eidse said. “She did so in a culture made up of people who themselves would avoid sitting with those people.

“I was so grateful to be able to follow my mother on her rounds and help her. It was an amazing experience to sit with leprosy patients who were weaving baskets by using their teeth.”

Eidse said she is indebted to a teacher who approved her plan to write a biology paper about the leprosarium where her mother worked.

“The experience was a great teacher,” she said.

And a fine start to a writing career.

Deeper Than African Soil

Interested in learning more about Eidse’s life? You can buy a copy of her memoir online at Amazon.com.