Glass Menagerie

Celebrating the history and future of an ancient art form

St. John’s Episcopal Church houses one of the most prominent collections of traditional stained-glass windows in Northwest Florida. Large vertical displays line the chapel with imagery significant to the Christian faith. Such imagery has been used in churches for hundreds of years to connect parishioners with the saints and stories of the past.

“I taught first grade Sunday school for years, and part of our lesson annually was to come in and listen to somebody tell us about the stained glass and have a scavenger hunt to find the symbols and stories used,” said Mandy Schnittker, director of communications for St. John’s.

While many of the windows in St. John’s have been dedicated by families within the last half century, several go back much further. The origins of the church’s oldest windows can be traced back to the mid-19th century.

“They are history unto themselves,” Schnittker said. “That history grows piece by piece, just as we add new windows over time.”

While often associated with the Christian faith, stained glass spans across several ceremonial and religious traditions. Like St. John’s, Temple Israel houses several vibrant works of stained glass. These windows, embossed with depictions of the Israelites’ pilgrimage through the desert, the Torah and representations of the Jewish calendar, express a more modern style.

In 2019, as part of extensive restorations to the church, St. John’s stained glass windows were preserved in order to ensure they can better withstand Florida’s heat, rain and wind for years to come. Bovard Studio, based out of Fairfield, Iowa, completed most of the stained glass and window repair and installed new vented protective glazing. Three windows were removed and restored in Bovard’s Studio, and a few smaller windows were taken to Iowa to have inscriptions, which had faded over the years, repainted by artists. Photo by Dennis Howard

Temple Israel’s largest stained-glass piece, a sprawling, colorful tree covered in raised handprints, was created by Florida State University’s Master Craftsman Studio, a hands-on arts program that focuses largely on stained glass. The window was commissioned by Temple Israel, said administrator Lisa Slaton, but the handprints were not part of the original design.

“We have a service once a year where we unroll the entire Torah,” Slaton said. “Everybody wears gloves or socks because you cannot touch the Torah directly. They are old and handwritten. That imagery really made an impression on him.”

FSU’s Master Craftsman Studio is housed in Dodd Hall, where many of its works are on display as part of the university’s Heritage Museum. Dozens of smaller windows honor significant aspects of FSU’s 171-year history, while two large installments on the front and rear of the building commemorate iconic university architecture and University President Emeritus Talbot “Sandy” D’Alemberte, who oversaw the inception of the Master Craftsman Studio in 2000.

“We want to see this craft go on after we are gone,” said Master Craftsman Studios Program Director John Raulerson.

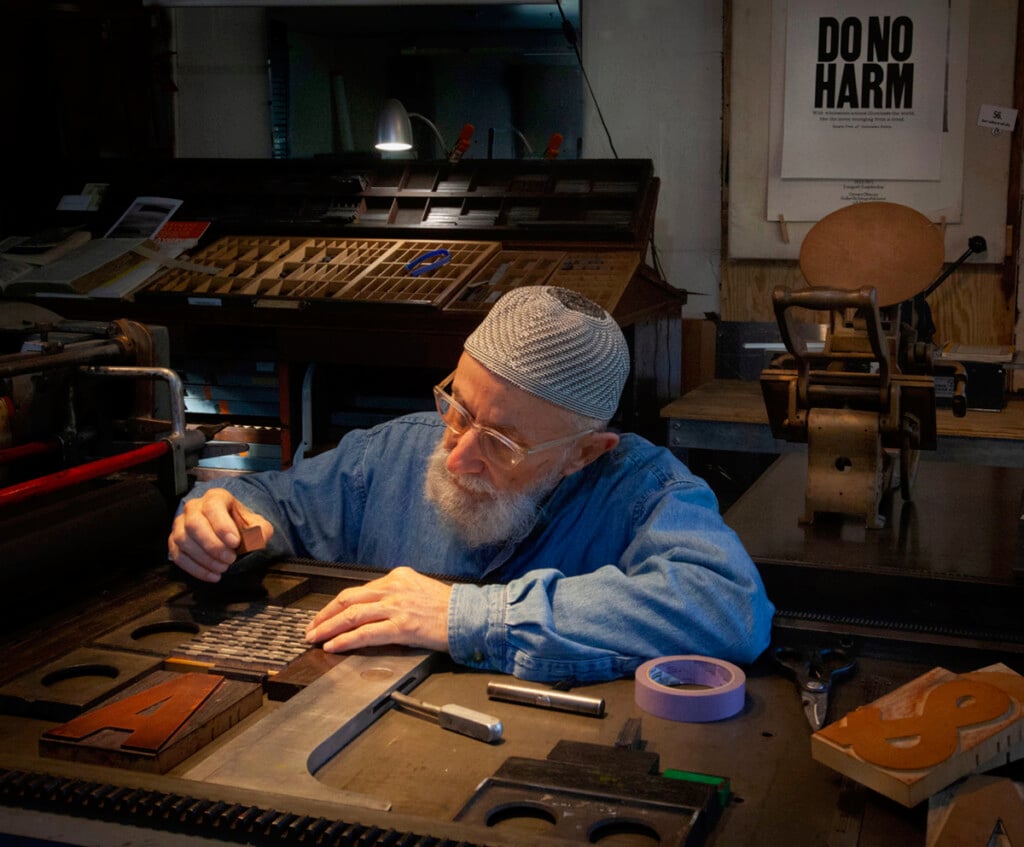

Like Raulerson, Andrew Miller is doing his part to keep the tradition of stained glass alive in the modern age. The Tallahassee stained glass artist and instructor at LeMoyne Arts has worked with stained glass for more than 30 years and has many repaired and original pieces in his own home.

“If I’m making something for myself, I am more interested in the abstract. However, when we are working in class, we usually do something a bit more traditional.”

Andrew Miller

Photo by Dave Barfield

In 1994, two dollars and a dose of overconfidence set Andrew Miller on an unexpected path. Miller was perusing a flea market near his Pittsburgh, Mississippi, home and stumbled across a charming, yet broken, stained glass window. Two crumbled bills later, and Miller resolved that he’d learn to fix the piece himself.

Miller sought the wisdom of a local glass dealer and took a course to learn the tools of the trade. He called antique stores across the state inquiring about damaged stained glass, and though most were reluctant to admit brokering in broken wares, he found a dealer in Jackson, Mississippi.

When Miller arrived at the warehouse, he was quickly ushered to a cracked window nearly eight feet tall and clearly out of his price range.

“Oh, that’s not for sale,” the dealer remarked. “I want you to fix it.”

Miller painstakingly repaired the piece and returned it to the dealer, who silently scrutinized his work.

“Of course, he knew what he was doing,” Miller said. “If you know old antique dealers, you know. Then he reached in his back pocket, pulled out this big wad of bills and started dealing some off. I could see those hundreds, you know. He had me.”

Miller went on to work for the dealer until his retirement in 2006. During that time, he also worked as an associate for Tiffany, restoring windows at a church in Maine.

Today, Miller’s home is filled with glass. In recent years, Miller brought his talent to LeMoyne Arts, where he teaches an eight-week course for beginners. Most of his restorations reflect a traditional style, but in his free time, Miller dabbles in contemporary designs with inspiration from architects like Frank Lloyd Wright.